The sad, greedy decline of network television

The sad, greedy decline of network television into games and circuses

But, oh, what a long, sad, downward journey it has been for the once-mighty media brands of NBC, CBS, ABC and Fox.

CBS and NBC all but invented TV as we know it in the late 1950s, and they were among the most dominant economic, cultural and political forces in the nation for half a century.

Each new fall season, they put forth an impressive array of new series that both reflected and shaped the popular culture. Their news divisions played as large a role as any single institution in setting the national agenda.

Presidents made decisions of war and peace based on what the people sitting at their anchor desks reported and said. The host of a news program, like Edward R. Murrow on “See It Now,” could expose the danger of a demagogue like Joe McCarthy, when even the president wouldn’t take on the reckless senator from Wisconsin.

Today, the networks are ragged ghosts of that greatness, featuring prime-time schedules filled with on-the-cheap game shows and endless reality competitions, culturally empty reboots of series that spoke to zeitgeists long gone, and news desks mostly anchored by forgettable cookie-cutter personalities who make Peter Jennings, Tom Brokaw, Dan Rather, Walter Cronkite and David Brinkley seem Olympian in memory.

Could you imagine any president saying, “If I’ve lost Jeff Glor, I’ve lost Middle America,” as Lyndon Johnson did of Cronkite after the CBS anchorman declared the Vietnam War a lost cause and urged an “honorable” withdrawal in a special telecast? (If you’re not sure who Glor is, my point has been made.)

If it weren’t for live sports events, like NBC’s “Sunday Night Football,” I can honestly say I would rarely tune to any of the networks for anything other than in my job as media critic.

I am not alone. The ratings news for the networks is dismal. But then, it has been dismal for more than a decade. Steady erosion has become year-to-year double-digit declines in audience, especially among viewers ages 18 to 49.

Last December, Ad Age ran an analysis headlined: “Has the bottom fallen out of the broadcast TV ratings?” Crunching Nielsen data, it reported a loss in network viewing of 16 percent year to year. The news for the first half of this season is not expected to be any better, according to analysts.

The promo that sent me down the path of this dark meditation aired during one of those live sporting events that I do still watch, NBC’s game between the Green Bay Packers and Minnesota Vikings last Sunday. It touted three series debuting, returning or both in January that were supposed to get me excited about the second half of the prime-time season on NBC: Dwayne Johnson’s “The Titan Games,” “Ellen’s Game of Games,” starring Ellen DeGeneres, and “America’s Got Talent: The Champions.”

That’s two more game shows and the spinoff of a summer replacement series. I can hardy wait.

According to NBC’s promo, Johnson’s show, which premieres Jan. 3, “will offer everyday people the once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to compete in epic head-to-head challenges designed to test the mind, body and heart.”

It goes on to say, “Those who can withstand the challenge have the chance to become a Titan and win a grand prize of $100,000.”

A grand prize of $100,000? NBC and CBS were giving away more than that on game shows in their infancy when they were struggling to find a national audience large enough to impress Madison Avenue and stay in business.

With no talent costs except Johnson, and $100,000 in “grand prize” money, the only question is: Could you do a prime-time show any cheaper?

As the network’s promo itself puts it: “DeGeneres serves as host and executive producer of the hour-long comedy game show, which includes supersized versions of the most popular and action-packed games from her award-winning daytime talk show.”

The big money here is $100,000 as well — not so supersized.

“America’s Got Talent: The Champions” debuts Jan. 7, though “debuts” might be stretching the meaning of the word in making it sound as if there is something substantially new here.

“Summer's hottest show, ‘America's Got Talent,’ is now ready to warm up winter!” NBC’s promo says. “This new spinoff features the most incredible and memorable acts from previous seasons ready to wow America all over again.”

Is there anything in that copy that does not say recycled, repurposed or repackaged? Maybe it’s just me, but I am not feeling the wow.

Sad to say, given the sorry state of network programming, these shows will probably do OK — better than, say, the reboot of “Magnum P.I.” on CBS. Although doing OK by network standards these days is a very low bar.

So, how did network TV become so diminished anyway?

There are a number of huge technological, sociological and lifestyle changes at play, which shredded the monopoly network TV enjoyed for decades thanks to friends in Congress. Probably the biggest single factor was new technology that allowed other platforms to end run the over-the-air control networks enjoyed as result of broadcast licenses issued by the Federal Communications Commission.

But I and many others have written volumes about that. What has not been so widely explored and explained is the way the networks, in their greed, gave away their journalistic and cultural dominance and authority.

By 2004, the networks were skipping entire nights of coverage to air summer reruns because they were more cost-effective. Summer reruns!

In 2008, when the nation had a rock star candidate in Barack Obama, the networks wanted to get back into the game. But it was too late: Cable, which had given the process of selecting presidential candidates the kind of time it deserved, owned the world of politics. Beyond the political and cultural authority and trust lost in that penny-pinching move were billions of dollars in political and other advertising that now goes to cable.

The same penny-wise network thinking led to the dearth of quality drama and surfeit of reality and game competition shows today.

I

Fontana came up in network TV as a writer on “St. Elsewhere” and showrunner on “Homicide: Life on the Street,” but the network industry preferred cheaper, cookie-cutter shows it could control and produce on assembly lines in its West Coast studios.

To get a great drama, you often had to deal with unpredictable, artistic creators and pay serious money to actors. While HBO and then streaming services like Netflix embraced such talent and endured big budgets to produce culturally relevant drama like “The Sopranos,” “The Wire” and “House of Cards,” the networks doubled down on cheap, highly manageable reality TV, competition and game shows.

And here we are today. How many network dramas do you still watch regularly besides NBC’s “This Is Us”?

But does it really matter that the networks betrayed their promise and now stink? New technology and cable and digital programmers have more than filled the void, resulting in a richer overall array of programs for American viewers, haven’t they?

Not for all viewers, unfortunately.

Just as there are two Americas when it comes to health care, college education, ability to buy a home and other quality-of-life matters, so it is with media options. For millions of Americans who cannot afford premium cable or streaming services, there are only the networks and our woefully underfunded public TV system. Those Americans who cannot afford the new designer channels and streaming services are being fed more and more junk food by the networks, which makes it impossible for them not just to enjoy the pleasures of quality programming, but to simply participate fully in this democracy.

I feel guilty every time I see a great documentary series, like “

What makes me so angry is that the networks were granted control of the public airwaves in the Communications Act of 1934 after promising Congress they would be good “stewards” — that’s the word executives and lobbyists used in their testimony — and broadcast in the public interest even as they pursued their corporate goals.

They lied, and 84 years later, we are still paying for their sins.

Audiences are declining for traditional news media in the U.S. – with some exceptions

A declining share of U.S. adults are following the news closely, according to recent Pew Research Center surveys. And audiences are shrinking for several older types of news media – such as local TV stations, most newspapers and public radio – even as they grow for newer platforms like podcasts, as well as for a few specific media brands.

Pew Research Center has long tracked trends in the news industry. In addition to asking survey questions about Americans’ news consumption habits, our State of the News Media project uses several other data sources to look at various aspects of the industry, including audience size, revenue and other metrics.

The latest data shows a complex picture. Here are some of our key findings:

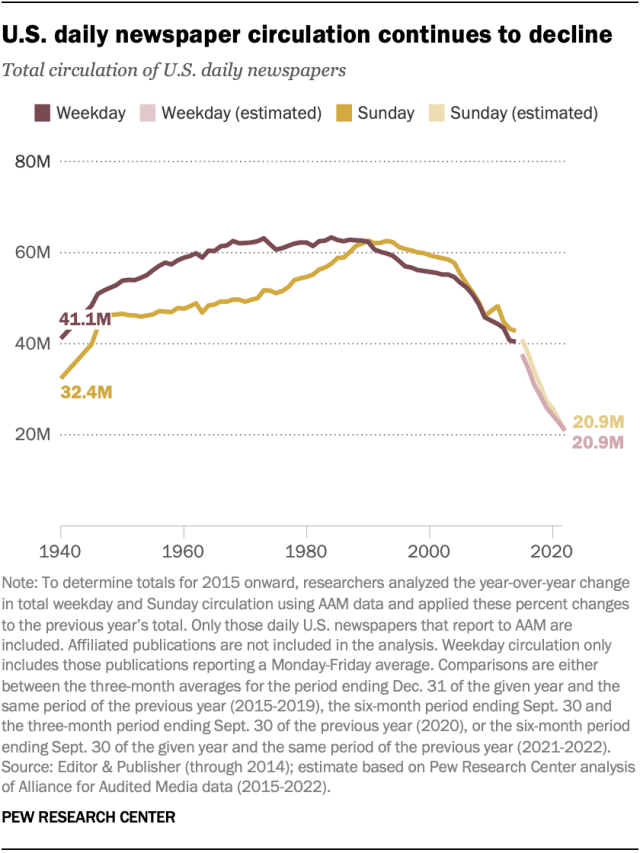

- For the most part, daily newspaper circulation nationwide – counting digital subscriptions and print circulation – continues to decline, falling to just under 21 million in 2022, according to projections using data from the Alliance for Audited Media (AAM). Weekday circulation is down 8% from the previous year and 32% from five years prior, when it was over 30 million. Out of 136 papers included in this analysis, 120 experienced declines in weekday circulation in 2022.

- While most newspapers in the United States are struggling, some of the biggest brands are experiencing digital growth. AAM data does not include all digital circulation to three of the nation’s most prominent newspapers: The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal and The Washington Post. But while all three are experiencing declines in their print subscriptions, other available data suggests substantial increases in digital subscriptions for The New York Times and The Wall Street Journal. (Similar data is not available for The Washington Post.) For example, The New York Times saw a 32% increase in digital-only subscriptions in 2022, surpassing 10 million subscribers and continuing years of growth, according to filings with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC). There are many reasons this data is not directly comparable with the AAM data, including the fact that some digital subscriptions to The New York Times do not include news and are limited to other products like cooking and games. Still, these brands are bucking the overall trend.

- Overall, digital traffic to newspapers’ websites is declining. The average monthly number of unique visitors to the websites of the country’s top 50 newspapers (based on circulation, and including The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal and The Washington Post) declined 20% to under 9 million in the fourth quarter of 2022, down from over 11 million in the same period in 2021, according to Comscore data. The length of the average visit to these sites is also falling – to just under a minute and a half in the last quarter of 2022.

- Traffic to top digital news websites is not picking up the slack. Overall, traffic to the most visited news websites – those with at least 10 million unique visitors per month in the fourth quarter of a given year – has declined over the past two years. The average number of monthly unique visitors to these sites was 3% lower in October-December 2022 than in the same period in 2021, following a 13% drop the year before that, according to Comscore. The length of the average visit to these sites is getting shorter, too. (These sites can include newspapers’ websites, such as that of The New York Times, as well as other digital news sites like those of CNN, Fox News or Axios.)

- https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2023/11/28/audiences-are-declining-for-traditional-news-media-in-the-us-with-some-exceptions/

No comments:

Post a Comment